The gift of engaging customer experiences

Customer experiences that are genuinely engaging are the gift organisations desperately want to receive. And it’s for life, not just for Christmas.

Some receive because first they give. There are others who will be disappointed because they have created a perception of taking rather than giving (Tesco in the UK for example). In doing so, they have undermined all the good stuff with wrong behaviours that customers watch and remember.

We know only too well that relationships are a two-way thing; they are not just price-led and they can be fragile. Any sign of contempt and that’s it. Over.

So it’s great to see those who are thriving by having the courage to adopt a “give to get” approach. They are not about short-term sales or how many followers they can get on Twitter. It’s not about blogging for blogging’s sake. It’s about sharing relevant information that will build a mutually beneficial, honest and empathetic connection with current and future customers.

To illustrate, here are four examples that I think are great role models.

TotalBlueSky/TotalRail/TotalPharma

From the stable of global conference company Terrapinn come three powerful event brands (there are more where they came from). They use quality videos to showcase their events but ensure the topics they cover are highly relevant to their audience and newsworthy. No great surprise there but even when there is no specific event to highlight or sell, they continue to create appropriate content, interviews with the people you want to hear from and insightful reports. A great way to keep up to date.

Websites www.totalbluesky.com | www.totalrail.org | www.totalbiopharma.com

Twitter @airlinesblog | @totalrail | @totalbiopharma

Speedo

These guys really show how to move from transactional to relationship-based engagement. More than a few of the world’s best swimmers use their kit so they could be forgiven for sitting back and letting that do the talking. But to their credit (and their commercial nous), taking prominence over the traditional shopping cart is Speedo World; experts tips and videos not just on how to swim faster, but techniques to be more efficient in the pool and in their words – how to feel wonderful, have fun and achieve your goals. It’s all brought to life even more so on their Facebook pages, a fantastic way to engage and stay front of mind for when that next purchase is needed.

Website www.speedo.com | www.facebook.com/speedo

Ian Golding

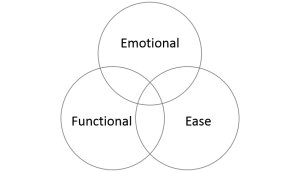

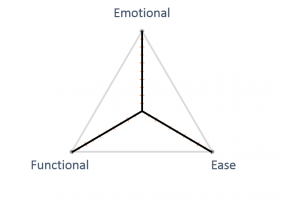

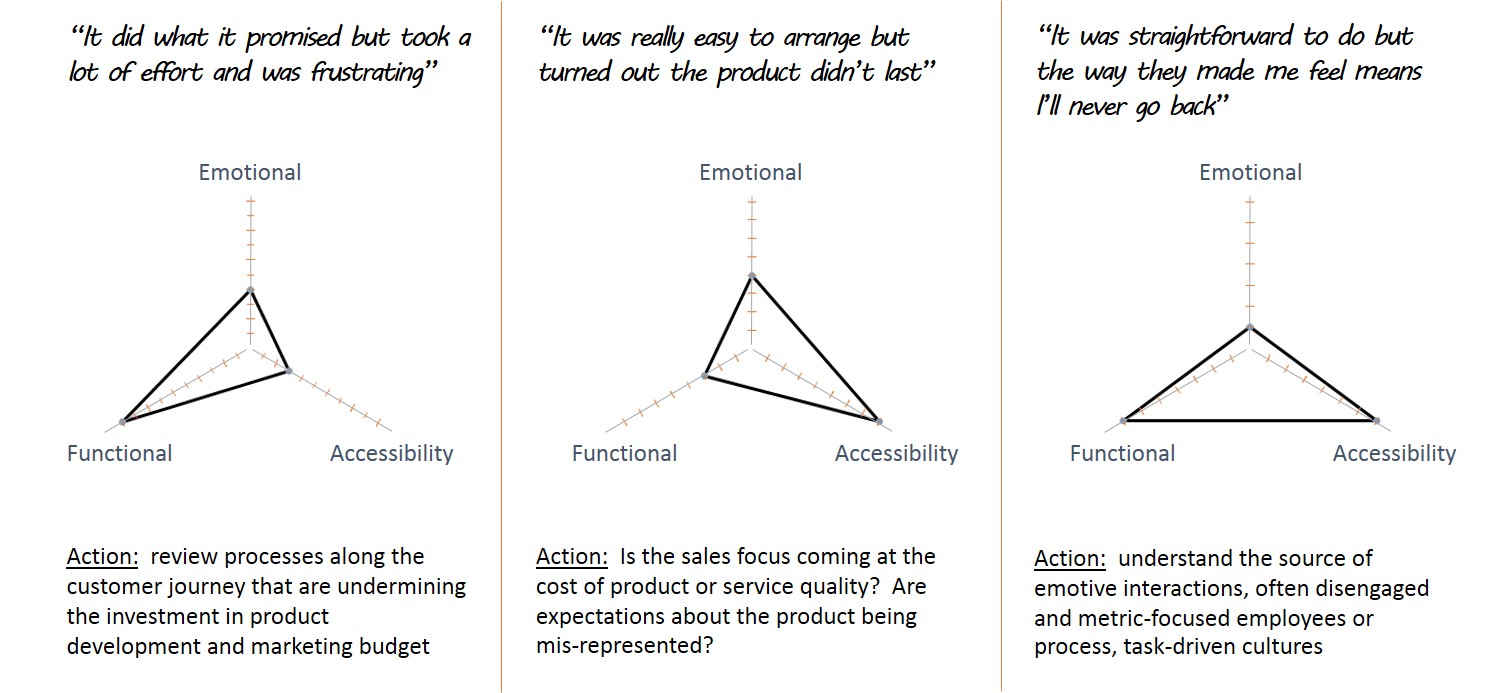

Fellow CCXP (Certified Customer Experience Professional), colleague and customer experience’s answer to Michelin’s restaurant reviews, Ian Golding is a relentless blogger. He writes about customer experiences he’s been on the receiving end of or has heard about from others. Ian applies a structured methodology to his reviews around the functional, ease and emotional consequences. What that creates is two things of real value to his readers; a wealth of cases studies on the good, the bad and the ugly of customer experiences and stimulating food-for-thought about how people can assess and improve their own organisation.

Website www.ijgolding.com

Twitter @ijgolding

Red Website Design

This UK-based company is another great example of sharing, in a way that’s relevant and profile-raising. For a start, their engagement on Twitter is two-way – they have over 147,000 followers and follow back nearly 130,000. Compare that with companies who enjoy tens of thousands of followers yet only reciprocate that to literally a handful. What does that say? I’ve included RWD here also because every day they post very practical tools and tips on how to improve websites and social engagement. They lead by example.

Website www.red-website-design.co.uk

Twitter @red_website_design

Creating differentiation and engagement by a offering high-value, low-cost proposition is a real commercial imperative. Not least, it involves and engages employees aswell as customers. And, by creating that connection at both an emotional and rational level, the certainty of having more customers, coming back more often, spending more and telling others about it is dramatically increased.

That then, is the gift that keeps on giving.

I’d love to hear your thoughts and examples of others you have seen – drop a note here or share them on Twitter, @Empathyce.

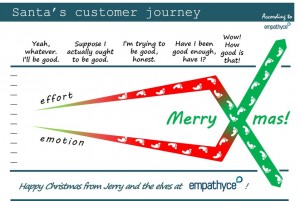

In the meantime, here is my small gift to thank you for reading, for your comments and for your company through the year.

Best wishes,

Jerry