Customer experience in the boardroom

Corporate change leads investors to rethink the potential for future income streams. But, by putting customer experience in the boardroom, can it improve that decision-making process?

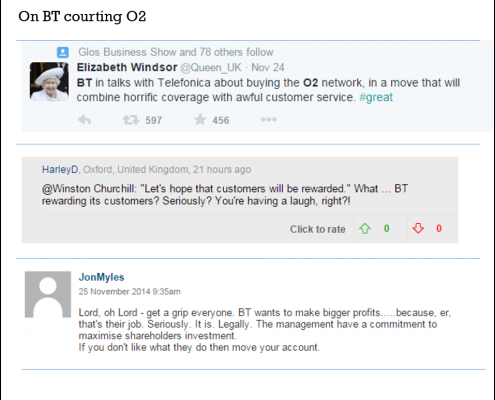

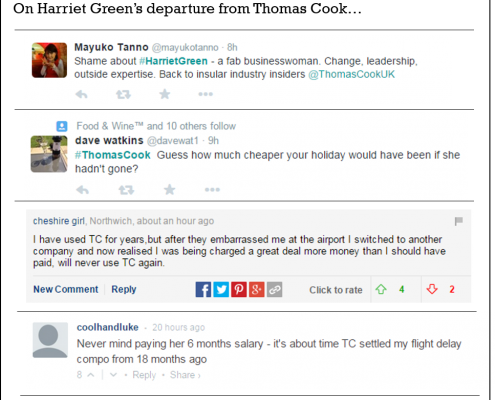

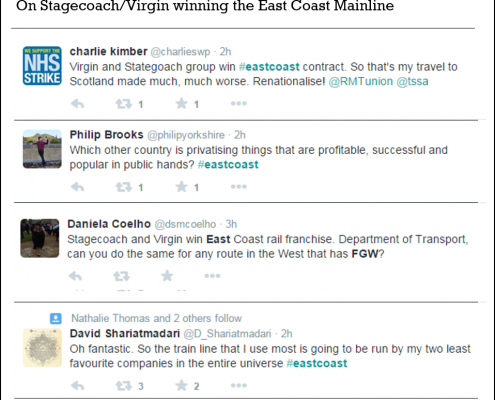

This week has seen some significant corporate activity in the UK. BT is making a play for the mobile market by talking to O2 about a return to its fold; Harriet Green made a surprise departure from Thomas Cook that sent its shares tumbling; And the East Coast Mainline rail franchise is coming out of public hands and into a combined Stagecoach and Virgin operator.

To make sense of these moves, we generally look to the stockmarket to see whether it’s good news or not. Fund managers crawl through a jigsaw of balance sheets, management profiles and annual reports to predict how this latest change will affect a company’s future cash flows, profitability and dividends. Within seconds, the outcome of that opinion is reflected in the share prices of those directly – and indirectly – involved.

There is though, a missing piece in that jigsaw and a critical one at that. I would say this wouldn’t I, but it’s the opinion of the customer. Why? A couple of reasons jump out.

Firstly, it is the customer who is going to be handing over the money that creates the revenue that underpins the profit that delivers the dividend. They can answer some very telling questions: How will these changes affect what they do? What else has it prompted them to share with others that will influence a wider audience? Why do they have the perception (whether rational or not) they do?

The answers to many of those questions arguably must provide a better forecast of a company’s future value. At the very least, an indication of what is going on at that front-line of that company. Or, early warning signs that having the strongest of capital ratios doesn’t necessarily mean that customers will come, come back, spend more and tell everyone they know to do the same. Here’s some examples of reactions this week; they have been selected to illustrate the point about underlying issues but have all been in the public domain.

That last line about changing provider sums up the issue nicely. Investors might be seeking the short-term profit but customers play the long-game, the implication being that investors will eventually lose as customers do have a choice. Two interdependent but not always aligned views.

The EastCoast rail franchise focus has been on the winners, yet other operators who were unsuccessful also get caught up in the conversations.

Secondly, these key stakeholders can just as easily be shareholders either directly or by association. They are just as informed, just as quick to pass judgement and, at the end of the day, are the ones who will determine whether the stockmarket called it correctly.

Investors are in the business of forecasting the future. So should they be better at listening to customers as if they were in the boardroom? Should they seek greater reinforcement or challenge to their investment decisions from the very people who will deal in reality, not predictions?