Airports and the people who use them want different versions of the same thing from the passenger experience. Whether we’re transiting through one or managing one, the common need is for it to be efficient. But this research report into what passengers tell each other about good and bad experiences shows that the way customers define efficiency is not always the same as how airports measure it.

- The ideal passenger experience is in airport that simply does what it’s supposed to and in a pleasant environment

- The consequences of long queues, inadequate facilities and the wrong staff attitude are what make people use a different airport next time

- An airport’s obsessive focus on processing efficiency risks doing the wrong things well and needing to spend resource on fixing self-inflicted problems

The gap between what airports think and what passengers think is a crucial one. All the while that metrics are being collated and analysed, if they are the wrong ones, airports will be oblivious to why passengers are exercising their choices and voices. In Barcelona last year, Andy Lester of Christchurch airport summed it up well when he talked of rebuilding after the 2011 New Zealand earthquake and observed

“If you think like an airport you’ll never understand your customers”.

We’ve seen recently a flurry of airports celebrating bigger passenger numbers and new routes with new airlines. Yet their customers react with a sigh because many of those airports are already at or beyond passenger numbers that make going through the airport a tolerable experience.

At the risk of generalising, airports aim to get as many people through the airport as possible, as efficiently as possible. It needs to be done in a way that means they can spend as much money as  possible, come back as often as possible and tell everyone they know to do the same. If it moves (that is either people or bags) they can barcoded, processed and measured. How many get from A to B in as little time or at least cost becomes the primary, sometimes, sole focus. All of which makes good operational sense, given the complexity and challenges of running an airport in a way that airlines will be confident is using.

possible, come back as often as possible and tell everyone they know to do the same. If it moves (that is either people or bags) they can barcoded, processed and measured. How many get from A to B in as little time or at least cost becomes the primary, sometimes, sole focus. All of which makes good operational sense, given the complexity and challenges of running an airport in a way that airlines will be confident is using.

But what are passengers concerned with and what is their version of what efficiency means? Kiosks with red, orange and green buttons greet us everywhere to ask how the service was. While that allows an AQS metric to be reported and tracked, there is no qualitative, actionable insight let alone allowances for mischievous kids or cleaners tapping away as they pass. However, the travel industry is blessed with no shortage of customers willing and able to give their feedback – and that in turn creates a vast reservoir of insight not only for customers choosing an airport but for the airports to tap into themselves.

From that readily available information I’ve researched to see what customers said to each other about what makes an airport good or bad. Using feedback on airports left at the Airline Quality / Skytrax review site I organised over 750 descriptions behind why passengers gave an airport a score of 9 or 10 (out of 10) and then 0 or 1.

Passenger experience key findings:

Where there were positive experiences, 98% of the comments can be summarised into one of two areas; either that it worked or that it was in a nice environment. That might seem obvious, and to a large degree it is. However, if it is so obvious then why are passengers still telling each other about cases where it’s anything but efficient?

What is it that customers tell each other when they write about the passenger experience?

The negative experiences were more fragmented in their causes, being about the function of the airport building, how good the processes in it are, staff attitude and information. What is clear is that a bad experience is significantly more negatively emotive than good experiences are positive. The core expectation is that everything will work as it’s meant to. If it does, great. But where it falls short, the consequences are commercially harmful, as typified by this message:

“I intend to avoid any lengthy stay in this airport again even if it means having to pay more to fly direct – it’s worth the price to keep your sanity”

In summary:

One: 55% of the reasons for a good score were simply about it being “efficient”

Airport experiences do not all have to have a Wow! factor. First and foremost, passengers just want everything to work. It’s a truism that without the basics in place being done well and consistently, a Wow! becomes a Waste of Work.

A noticeable number of passengers used the word “efficient” in their reviews, by which they were referring to things such as (in order of how often these were mentioned)

- there was almost no experience, in that everything worked as it should

- when they needed to interact with staff, the response was courteous and helpful

- getting around the airport was easy because of good signage and easily accessible information

- they didn’t have to wait long on arrival to collect bags and head on the next leg of their journey

- getting to and from the airport was easy, with good connections and acceptable parking charges

Two: 43% of the reasons for a good score were about a nice airport environment

The most efficient, effective, high-tech and innovative processes will all have their business-case ROI ruined if the environment in which they operate makes people feel like they are being treated with contempt. Often that happens unintentionally but if the value-exchange is one-sided, there is only so long a customer will put up with it. Chances are they have spent a lot of time and money on this trip, they are by definition not yet where they want to be and anything that is perceived as not making their journey any easier will count against the airport. It puts into context why people value a pleasant environment, the most common specific examples of which included:

- shops were relevant, toilets were sufficient in number and the general facilities laid on were good

- everywhere was kept clean and tidy

- the layout was spacious with plenty of comfortable seating

- the atmosphere throughout was one of calm, bright and quiet

- good wi-fi connections were cited but this is increasingly sliding down the food-chain to be a basic expectation; its absence being more of an issue than its presence.

What do they say when the experience is a good one? Here are some examples:

“It’s clean. It makes you believe they are aware of their customers’ health and wellbeing”

“If you have the option to use this airport, it is a great choice”

“It never lets me down”

Three: 48% of the negative reasons were about the facilities

Where customers were giving airports a score of 0 or 1, the biggest gripe was that the airport couldn’t cope with the volume of passengers. The resulting slow and uncomfortable journey through the airport creates frustration and anxiety. It’s made worse by the fact that as passengers we not unreasonably expect airports to know exactly who is going to be in the airport each day and to be prepared. Other consequences of the over-crowding included poor seating, a dirty and gloomy atmosphere and poor choices of food and drink.

It’s for these reasons that an airport celebrating a rise in new passenger numbers might want to acknowledge and address the concerns of existing customers at the same time.

Four: 28% of the negative reasons were about processes

For passengers, security, immigration and baggage handling fall into the category of processes that should just work every time. Where they do, it’s fine, but where they fall short, they can have a significant impact on influencing whether a passenger will choose that airport again.

Slow moving queues, duty free goods being confiscated in transit, poorly translated instructions and slow baggage reclaims were among the specific processes that riled customers. Again, it becomes emotive because these are all seen as avoidable inconveniences when we experience other airports who can and do get it right.

Five: 13% of the negative reasons were about staff

As a generally compliant travelling public (and I accept there are exceptions, such as when peanuts are served in bags), going through an airport can be a daunting experience even in the best of terminals. The one thing we hope we can rely on is that when we need to interact with another human being there will be a mutual respect, a helping hand or at least clear instructions so we can indeed be compliant. Airports go out of their way to train staff and yet the evidence is that many are still failing.

Rude, unempathetic, incompetent, unhelpful, deliberately slow and uncaring are just some of the ways staff were described. Any organisation is dependent on having good relationships but where one side feels they are being treated with contempt, it becomes a very deep scar to heal.

A customer wrote about their disappointing and surprising experience at one of the largest US airports where there were

“Miserable, nasty employees, barking and screaming at customers as if they were dogs”.

Good news – plenty of seats. Bad news – information boards positioned too far away beyond the moving walkway

Six: 11% of the negative reasons were about information

It’s an area airports have focused on and with a good deal of success. Making passengers more self-sufficient and having employees being better at handling questions has benefits for all sides. But there are still airports where having the right information at the right time in the right place is still elusive; more specifically, passengers concerns around information was that either there was none, it was inadequate, it was wrong or it was confusing – all frustrating when we live in a world dominated by technology and information.

So what? Why is it important and what does it tell us?

- Poor experiences make people choose other airports next time. Passengers’ expectations are not only set by what it was like last time, but by how other airports do it and by their interactions with other companies they deal with in their day-to-day lives. So where things don’t meet the basic expectations, not only does that impact on revenue for the airport there is also a commercial consequence for airline partners. For example, some passengers said

“I usually fly Delta but will now try to avoid them – to avoid Atlanta”, and

“Because of this airport I will never fly Etihad again”

- Depending on which piece of research you read, anything between 75% and 95% of customers are influenced by what others say. Any robust customer strategy will have at its core a clear vision of what the experiences need to be in order that passengers will think, feel, do and share as intended. Many organisations now build into their customer journey mapping a stage specifically to address the “I’m sharing what it was like” issues.

- An obsession with metric-driven efficiency and processes that work for the airport’s operations team but not for passengers creates blind-spots as to what will help drive non-aeronautical revenue. Customers themselves recognised this by saying

“All of time put aside to shop was spent queueing”, and

“They have allowed way too many people to use this place. Cannot be good for business as nobody has time to spend any money in the shops or bars”

Declan Collier of London City Airport reinforces the point about the dangers of process focus, task orientation and metric myopia when he talks about being “in the people business” and that the fortunes of LCY will “rise or fall on the ability of its people”.

For example, last year I questioned the fanfare for an app that tells passengers where their lost bags are. I accept that bags go missing but as a passenger, whether I’ve a smart-phone and free hands or not, I’d prefer to have seen the investment directed to not leaving me feeling awkward and helpless standing by an empty baggage carousel. However, I was told by a large airport hub that the rationale was that it would mean transiting passengers could run for their connection without having to worry about collecting bags that weren’t there. I was told that yes, running is part of the expected experience and my concerns about what that is like for my confused mother or my autistic son fell on deaf ears. I was told I don’t understand airport operations and they’re right, I don’t. But I do understand what it’s like to be a passenger.

- The best airport experiences don’t need to be expensive, complex or high-tech. Think what a difference just having engaged, helpful and friendly staff makes – and that doesn’t take a huge piece of capex to justify, just a degree of collaboration with employees and third parties who have the airport’s brand reputation in their hands.

- One observation in the course of the research was that the high and low scores often applied to the same airports. That has to be a concern and worthy of investigating; why can it be done so well at times but not at others? How come all the effort and pride can create advocates some of the time but at other times is just handing passengers to competitors?

Final thoughts on the airport passenger experience

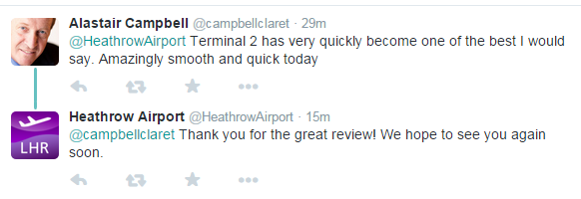

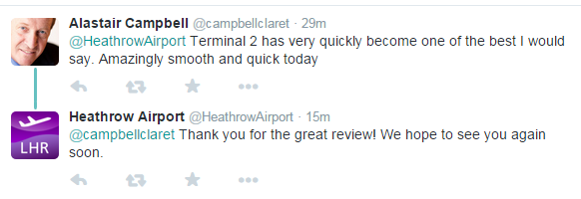

These days, people do not expect a poor passenger experience. The bar is climbing higher and in simple terms that just means doing the right things well. Earlier this year, writer Alastair Campbell travelled through Terminal 2 and sent this tweet to his 285,000 followers:

Unsurprisngly, Heathrow’s social media team proudly retweeted it to a similar number of their followers. Within 15 minutes, this positive message was shared with well over half a million people. And all because the experience was simply – and “amazingly” – smooth and quick. Nothing more complicated than that.

It’s not just about giving customers the right experiences every time. To make an airport efficient for passengers as well as managers it also needs to avoid giving the wrong experiences, ever. The commercial consequences are riding on it.

Passengers know that as well as anyone. So if there’s one message, then it is that the airport and its brand is only as good as people tell each other it is.

I hope you find this report useful and interesting but email [email protected] or call me on +44 (0) 7917 718 072 if you’ve any questions or comments – I’d love to hear your views.

Thank you,

Jerry Angrave

possible, come back as often as possible and tell everyone they know to do the same. If it moves (that is either people or bags) they can barcoded, processed and measured. How many get from A to B in as little time or at least cost becomes the primary, sometimes, sole focus. All of which makes good operational sense, given the complexity and challenges of running an airport in a way that airlines will be confident is using.

possible, come back as often as possible and tell everyone they know to do the same. If it moves (that is either people or bags) they can barcoded, processed and measured. How many get from A to B in as little time or at least cost becomes the primary, sometimes, sole focus. All of which makes good operational sense, given the complexity and challenges of running an airport in a way that airlines will be confident is using.